I’ve been to national parks all over the world, including: Kakadu National Park in Australia; Kruger National Park in South Africa; Masada National Park in Israel; Giant Panda National Park in China, and national parks in Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, Colombia, Costa Rica and Canada. I’ve also been to some of the 63 national parks in the United States, where the whole idea of a national park originated.

It started 1872 when President Ulysses S. Grant signed an order to set aside a 3,500-square foot tract of land in the area around Yellowstone Lake and Yellowstone Caldera as federal territory reserved for recreational use of the people. That made Yellowstone the first national park. But Yellowstone actually had a predecessor. The first time land was set aside by the federal government for the people was in 1864 under President Abraham Lincoln. That land was what is now Yosemite National Park. Yosemite was the precedent that opened the possibility of what developed into the National Parks.

It happened via The Yosemite Grant Act, a bill proposed by California Senator John Conness and signed into law by Lincoln on June 30, 1864, while the Civil War was still raging. The law gave the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove to the state of California, with the stipulation that it be reserved for public use and recreation. The 1,200-square mile area in the Sierra Nevada Mountains started as a state park and became the third national park on October 1, 1890, 18 years after Yellowstone. But in a sense it was the first. Yosemite was the prototype of the National Park system.

What could be so special that could gather the force required to push through such a hugely significant precedent, one that would set up a new kind of entity that would then be adopted around the world?

One has to experience at least one of the great national parks to understand the reason for the whole idea. Yosemite is a place of such staggering beauty that just to see it is spiritually uplifting. It’s known for giant monolithic mountains of granite, huge sequoia trees thousands of years old, and dramatic waterfalls that shoot off towering cliffs and fall freely through space into plunging valleys.

And rainbows at night! It’s one of the only places where moonlight sometimes lights up the mists from the waterfalls and makes rainbows at night. Just to see Yosemite is to understand why it was worth such a struggle for some people to make sure the parklands were protected. Hopefully, because of that action, the people of the future will still be able to enjoy that beauty as previous generations have.

All the national parks are beautiful in their own ways. They had to be to get through the battle to achieve that protected status. But Yosemite is a very special one, not only because it was the first to be set aside, but also because it was known to be the favorite place of John Muir, a man often credited as the father of the national parks, and one of the greatest champions of conservation in American history.

Muir moved with his parents from Scotland to Wisconsin when he was 11 years old. After being almost blinded in an industrial accident as a factory worker, Muir had a kind of conversion. He set out to learn as much as he could about the landscape of the earth before it had been altered by human settlements and industry.

For a while he studied natural sciences at the University of Wisconsin, but he had little patience with academia, preferring to spend his time in the “University of the Wilderness.”

He first visited Yosemite in 1868. To support himself there, he worked a series of jobs: as a ranch hand, a shepherd and a worker in a sawmill. He built a cabin close to Yosemite Creek so he could hear the sound of flowing water as he slept. But he was appalled by the destruction perpetrated by careless people trashing the landscape, stealing its natural resources. He became determined to do something about it.

Muir wrote, “The great wilds of our country, once held to be boundless and inexhaustible, are being rapidly invaded and overrun in every direction, and everything destructible is being destroyed. How far destruction may go is not easy to guess. Every landscape low and high seems doomed to be trampled and harried.”

The Yosemite Valley had been inhabited by Native Americans, the Miwok people, for 4,000 years. It had been nicely preserved until the Gold Rush of 1849 flooded the Sierra Nevada mountain range with people obsessed with gold and the dream of instant riches.

It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like for people whose ancestors had been living on that land for millennia when they were suddenly fallen upon by hordes of rapacious men in a mad quest to dig gold out of the earth.

The inevitable clashes between natives and miners escalated rapidly to a state of war. In 1851, the incoming settlers organized a battalion of volunteers, who attacked the Miwok people, burned villages and destroyed food supplies, eventually running them off the land.

It’s an ugly page in history, but there is some redemption in the fact that there were also people who took action to prevent more of the destruction that was taking place in the Yosemite Valley. It was their activism that led to the Yosemite Land Grant that Lincoln signed.

Unfortunately, it took more than a law to protect the land. Laws are only as good as their enforcement, and the law did not provide the means to enforce it.

That’s where John Muir comes into the story. He was a colorful figure, an eloquent and imaginative writer, who was able to use his gift to proselytize for the preservation of nature’s greatest beauties.

The success of the conservation movement in leading to the creation and maintenance of today’s national park system is the result of the efforts of multitudes of people. No one did it alone. But John Muir does have a very special place in that history.

In 1868 Muir walked from San Francisco Bay to Yosemite Valley, a distance of more than 180 miles. He wrote about his journey and published articles about Yosemite in magazines and newspapers across America.

In spite of Yosemite’s protected status, it was being overrun. It was being used for grazing by cattle farmers and for lumber by logging operations. Muir’s articles helped to ignite a conservation movement. He became a kind of tour guide, escorting influential people to the area to convince them to join the cause of protecting the wilderness from destruction for short-term profit.

On one of his trips Muir hosted Robert Underwood, editor of Century Magazine. During the trip they decided to launch a campaign to make Yosemite a national park. The campaign achieved its aim in 1890.

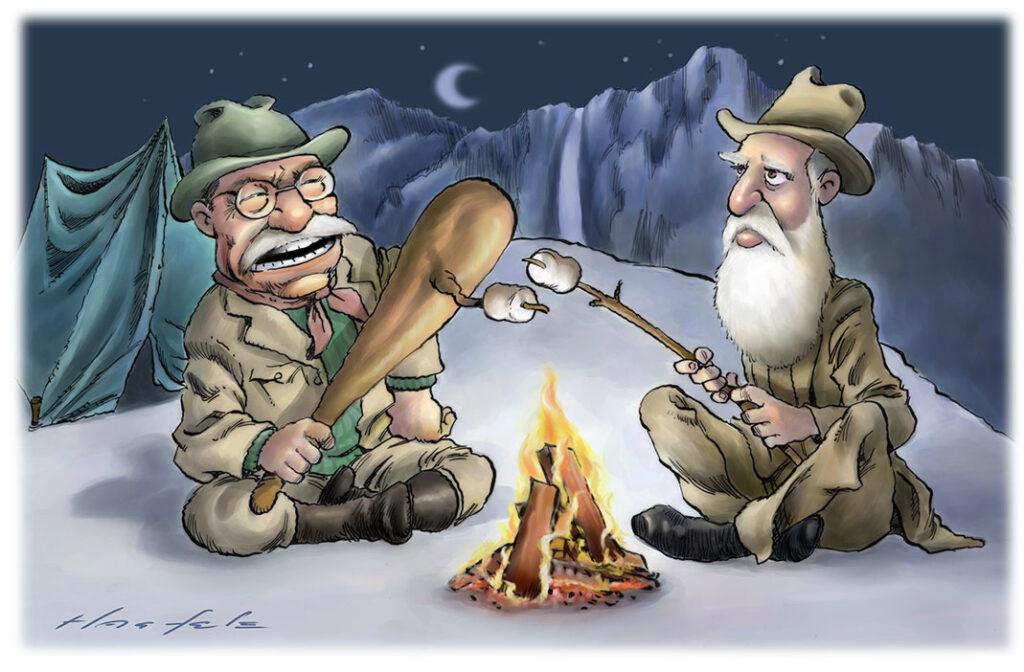

But even after achieving national park status the area was still effectively under attack by people appropriating its resources to produce personal wealth. In 1903, Muir took Teddy Roosevelt, who was the sitting president, on a camping trip in the Yosemite Valley. It inspired Roosevelt to take action in 1906 to take control of the park from the state and put it under the jurisdiction of federal government.

Roosevelt had similar sympathies to Muir regarding nature, and went on to sign into existence five national parks, 18 national monuments, 55 national bird sanctuaries and wildlife refuges, and 150 national forests. The creation of the National Park Service, to set up the means to actually protect the parks, would take place under a later president, Woodrow Wilson, in 1916.

Each of the national parks and reserves is individually precious, and the whole institution is one of the greatest legacies to which people around the world are now heirs. It’s really something to be grateful for. I hope we could all learn from the accident that almost blinded John Muir and sent him on his quest into the wilderness, and try to realize that life is short, and it is worthwhile to see as much of that beauty as possible.

Your humble reporter,

Colin Treadwell